Essay by Rex Weil

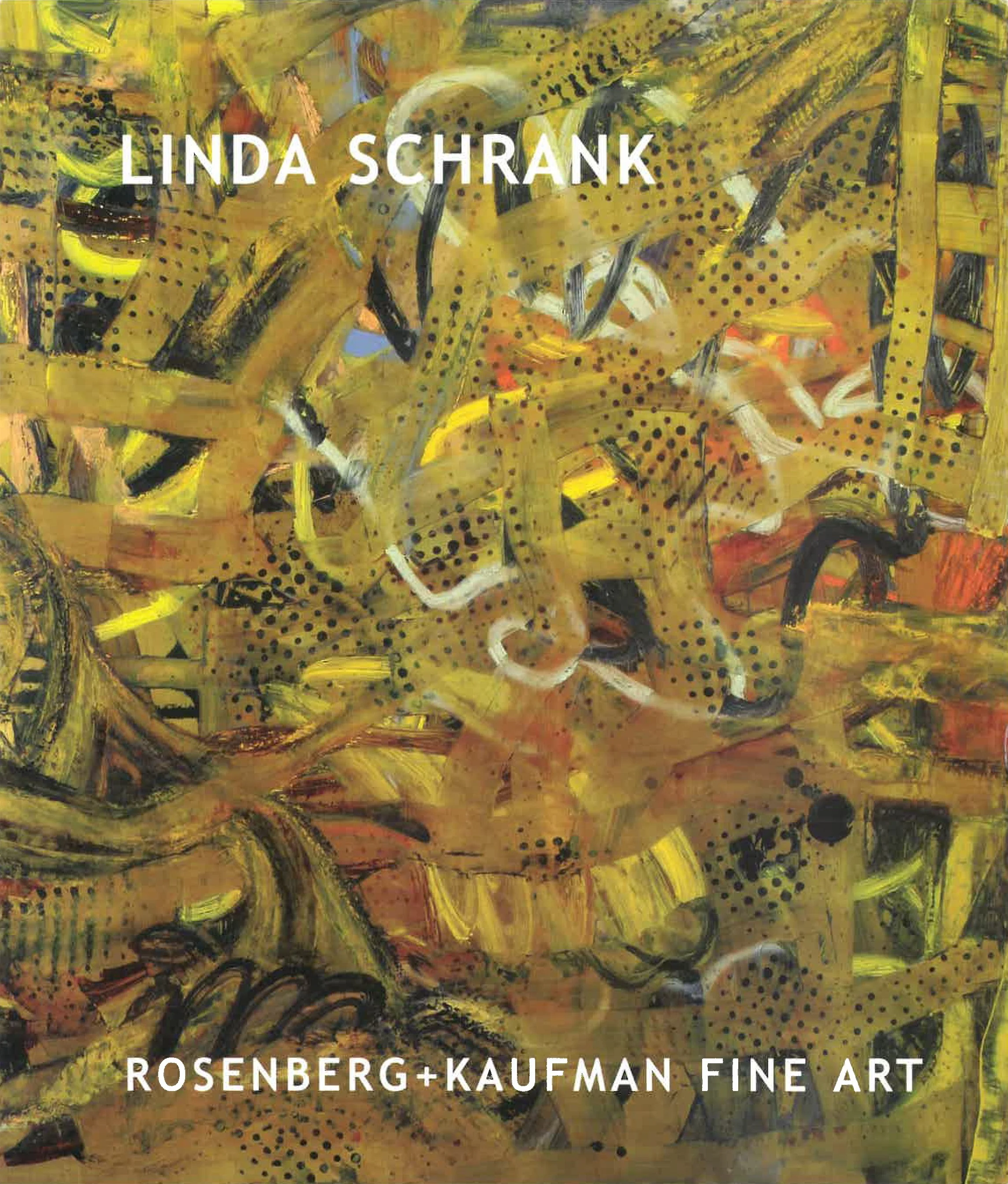

Linda Schrank's ambitious, energetic new work simultaneously embraces and attacks the painterly conundrum of creating space on a flat surface. Pulling out all the stops, Schrank brings to bear not only her formidable experience and painterly practice, but also an arsenal of eclectic influences and passions, including, among others, Indian miniatures, Sienese paintings, Benin sculpture, Piero della Francesca, Cézanne, Klee and Guston. Schrank's effortless blending of modernism with the rhythmic force of other traditions and times -- a process Charles Jencks calls 'double coding' -- underscores her alignment with the most advanced and progressive tendencies in contempo- rary painting. Along the way, she also introduces into her work two fascinating formal inven- tions that tear open and complicate the marvelous tightly woven compositions of recent years. Now, Schrank's seemingly impenetrable places are punctured and probed by fresh, peripatetic lines and grids of glossy, shellac dots. Full of paradox and surprises, the new paintings depict spaces as delicate and shallow as a heap of ribbons on a table, gently lifted by a breeze and as deep and intimidating as an ocean lying beneath the surface of waves.

Line on a Walk emphatically declares Schrank’s new approach. A sinuous, vein of white gracefully curls and wrestles through a thicket of broader bands of yellow and orange. This humble line's task would have required a machete in Schrank's densely packed paintings of several years ago (for example, Aswarm (2003), where the gorgeous bands of color are as unyieldingly intertwined as a mangrove). The new painting's title refers to Klee and the work clearly pays homage to the Swiss artist's playful animation and burnished colors. The black dots, though, imply something else: a zooming-in among the interstices of Schrank's strokes. We are closer, deeper, more intimately inside Schrank’s pictorial space than ever before. Perhaps, the dots were always there, we just could not see them. Did our percep- tion of closely wrapped surfaces simply reflect our perceptual prejudice in favor of the illu- sion of solidity that makes the world negotiable? The floating dots leave that illusion in tat- ters, suggesting instead a dizzying Dionysian experience of being-in-the-world. Matter is, after all, as science teaches, in constant motion -- a vast network of loosely connected, electronically charged particles.

In Plummet, the feeling of inward motion is amplified and accelerated. The punning title captures both the action of the piece and its dominant color: We plunge through bands of purple tones that appear, alternately, as supple as flayed skin and as hard and shiny as a Gehry exterior. Nonetheless, it is a weightless, almost contented fall – like Alice down the rabbit hole. We feel secure that, for Schrank, there is always surface within surface, system within system -- always a place to land. Each dot may contain a new level of complexity as immense and destabilizing as the one in which it is seemingly contained.

In Rhizome, Schrank accentuates the organic, biological aspects of her new compositions. The title indicates a complex root system. Creeping lines function as the paths of roots struggling and pushing -- searching for nourishment and at the same time therapeutically aer- ating the depths for other new life. Here, warm, lustrous yellow-browns suggest ginger, which is, literally, a rhizome.

Schrank’s investigations and her rich eclecticism do not acknowledge a need for final resolu- tion, perfection, or a totalized, reified order of things. Like her rhizome, she keeps reaching and penetrating, finding only new frontiers for exploration, new levels of paradox. Fortunately, Schrank has the confidence, skill and refinement to eschew illusory order in favor of intellectual and aesthetic openness. We are, it seems, ruled by aggressive posi- tivists for whom every question requires a quick, simple answer. As a remedy, openness is just what is called for. Herbert Marcuse, in his 1977 The Aesthetic Dimension, argues that the experience of art can provoke a subtle, liberating shift in subjective consciousness by "breaking through mystified, petrified social reality and opening the horizon of change." That is precisely what these paintings do.

________________________________________________________________________________________________

Rex Weil is an artist, educator and writer living and working in Washington, DC. He is a contributing editor of ARTnews and teaches theory and criticism at the University of Maryland, College Park.